Sherlock Holmes: The Devil's Daughter Review

June 16, 2016 | 10:05

Companies: #bigben-interactive #frogwares

The abysmal portrayal of Holmes sort of defeats the point of the game before it has properly begun. But I could possibly forgive it if The Devil’s Daughter was a quality detective game. Sadly, it’s so bad in so many ways that I’m not even sure where to start.

I think, broadly, the problem is that The Devil’s Daughter has almost no coherent systems, instead adopting a "kitchen sink" approach to design. Let’s take the first case as an example, in which Holmes is enlisted to help a young street urchin find his missing father. Alongside the multiple detective systems the game has, which we’ll get to in a minute, The Devil’s Daughter also includes puzzle platforming, a sprinkling of rudimentary cover shooting, stealth sections, chase sequences, dialogue choices, and about a half dozen other ideas.

Sounds great, right? Sadly not. Many of these mechanics are used once or twice before being completely discarded, while many sequences in the game are based on teeth-gratingly bad minigames. In one example, Holmes must eavesdrop on conversations to identify a man in a pub who is offering 'Special Jobs' to poorer residents of London. To do this, you must manipulate the mouse and keyboard to keep two wandering reticules in their respective circles. If you’re successful, the men you’re eavesdropping on will spit out a single sentence about the man you’re looking for, like 'he has mutton chop whiskers' or 'he doesn’t drink alcohol.' It’s about as subtle as a rhinoceros trying to sneak across a floor lined with bubble-wrap.

After this, there’s an agonisingly long sequence in which Holmes’ young associate, Wiggins, has to follow the man identified by Holmes. Assuming control of Wiggins, you must hide behind cover every five seconds while the man stops and takes a long look behind him - you know, just how people walk around in real life. Within this minigame are several smaller minigames. You have to climb a chimney while chipping soot off the flue, and balance across a beam using the same wavy reticule mechanic used in the eavesdropping section.

So The Devil’s Daughter proceeds, minigame after minigame after mechanic after minigame. This would be fine if the minigames were, A) fun to play, and B) had a worthwhile payoff, but they aren’t and don’t. What’s more, almost every action you do has to be accompanied by some sort of minigame, no matter how insignificant to the larger picture. One, in which you play as Holmes’ dog, Toby, to follow a scent, was so appalling that I had to stop playing because I was laughing so hard. Toby isn’t animated properly and controls like a tank, so he rotates on the spot when turning without moving his legs, and glides staircases like a ghost on a stair-lift. There’s even an entire minigame built for a three-second vignette in which Holmes swings across a gap using a dangling chain. The Devil’s Daughter might be the first game ever that I wished had more cutscenes in it.

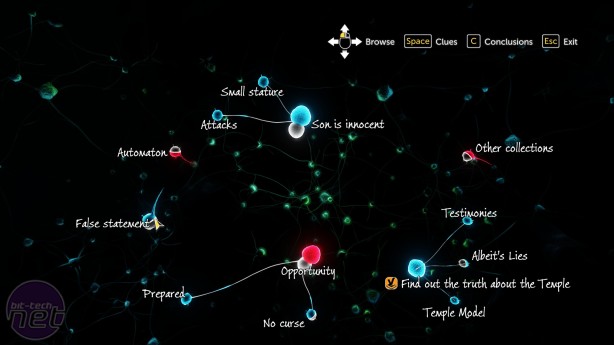

What’s particularly galling about all this mechanical frippery is that the central ideas revolving around being a goddamned detective actually have potential. The deduction mechanic, wherein you enter the mind of Holmes and connect clues to form theories, is a splendid idea that ought to be the focus of the game, letting you experiment with different connections and collect lots of clues to narrow-down the range of possible options. Instead, what you get is a far more limited system that only allows connections between specific clues, thus forcing you to work with the developer’s rather squiffy logic. I got the solution to the first case completely wrong, because the game never bothered to explain that you can come to multiple conclusions.

The same goes for other systems, like establishing a summary of a character through observing their appearance, which only offers you optional deductions sometimes, and isn’t always clear whether it’s offering you a choice or not. You can also counter certain statements made by a character with a piece of contradictory evidence. But the trigger for this is terribly signposted, ambushing you with a ticking timer when this ability is available to you, without actually explaining how you’re supposed to respond. But then, it lets you take as long as you like to actually choose from the range of options.

These could be brilliant systems for a detective game, but they’re simply too inconsistent to be enjoyable. Instead of building the game around these deductive systems, The Devil’s Daughter simply throws them atop the mounting pile of mediocre mechanics. Even the story is damaged by the constant systemic switcheroos. At one point, Holmes decides to visit Epping Forest as part of his investigation. But in the very next scene he’s being chased by an unseen maniac wielding a shotgun with no context given for how this situation arose. In another case, Holmes finds a model of an Aztec temple which forms part of a larger contraption. But when he connects the two, the following scene suddenly sees Holmes inside the model, at which point you’re forced to proceed through an interminably long sequence of half-baked environmental puzzles. It’s absolutely all over the place.

My only conclusion is that Frogwares’s ambition got the better of it. It seems to have gone completely mad and attempted to include every idea it had into the Devil’s Daughter. The result is a brown and broken mess that I never once enjoyed. It’s a smorgasbord of nonsense, a cornucopia in which all the food has rotted. And what do we do with something rotten? We put it in the -

I think, broadly, the problem is that The Devil’s Daughter has almost no coherent systems, instead adopting a "kitchen sink" approach to design. Let’s take the first case as an example, in which Holmes is enlisted to help a young street urchin find his missing father. Alongside the multiple detective systems the game has, which we’ll get to in a minute, The Devil’s Daughter also includes puzzle platforming, a sprinkling of rudimentary cover shooting, stealth sections, chase sequences, dialogue choices, and about a half dozen other ideas.

Sounds great, right? Sadly not. Many of these mechanics are used once or twice before being completely discarded, while many sequences in the game are based on teeth-gratingly bad minigames. In one example, Holmes must eavesdrop on conversations to identify a man in a pub who is offering 'Special Jobs' to poorer residents of London. To do this, you must manipulate the mouse and keyboard to keep two wandering reticules in their respective circles. If you’re successful, the men you’re eavesdropping on will spit out a single sentence about the man you’re looking for, like 'he has mutton chop whiskers' or 'he doesn’t drink alcohol.' It’s about as subtle as a rhinoceros trying to sneak across a floor lined with bubble-wrap.

After this, there’s an agonisingly long sequence in which Holmes’ young associate, Wiggins, has to follow the man identified by Holmes. Assuming control of Wiggins, you must hide behind cover every five seconds while the man stops and takes a long look behind him - you know, just how people walk around in real life. Within this minigame are several smaller minigames. You have to climb a chimney while chipping soot off the flue, and balance across a beam using the same wavy reticule mechanic used in the eavesdropping section.

So The Devil’s Daughter proceeds, minigame after minigame after mechanic after minigame. This would be fine if the minigames were, A) fun to play, and B) had a worthwhile payoff, but they aren’t and don’t. What’s more, almost every action you do has to be accompanied by some sort of minigame, no matter how insignificant to the larger picture. One, in which you play as Holmes’ dog, Toby, to follow a scent, was so appalling that I had to stop playing because I was laughing so hard. Toby isn’t animated properly and controls like a tank, so he rotates on the spot when turning without moving his legs, and glides staircases like a ghost on a stair-lift. There’s even an entire minigame built for a three-second vignette in which Holmes swings across a gap using a dangling chain. The Devil’s Daughter might be the first game ever that I wished had more cutscenes in it.

What’s particularly galling about all this mechanical frippery is that the central ideas revolving around being a goddamned detective actually have potential. The deduction mechanic, wherein you enter the mind of Holmes and connect clues to form theories, is a splendid idea that ought to be the focus of the game, letting you experiment with different connections and collect lots of clues to narrow-down the range of possible options. Instead, what you get is a far more limited system that only allows connections between specific clues, thus forcing you to work with the developer’s rather squiffy logic. I got the solution to the first case completely wrong, because the game never bothered to explain that you can come to multiple conclusions.

The same goes for other systems, like establishing a summary of a character through observing their appearance, which only offers you optional deductions sometimes, and isn’t always clear whether it’s offering you a choice or not. You can also counter certain statements made by a character with a piece of contradictory evidence. But the trigger for this is terribly signposted, ambushing you with a ticking timer when this ability is available to you, without actually explaining how you’re supposed to respond. But then, it lets you take as long as you like to actually choose from the range of options.

These could be brilliant systems for a detective game, but they’re simply too inconsistent to be enjoyable. Instead of building the game around these deductive systems, The Devil’s Daughter simply throws them atop the mounting pile of mediocre mechanics. Even the story is damaged by the constant systemic switcheroos. At one point, Holmes decides to visit Epping Forest as part of his investigation. But in the very next scene he’s being chased by an unseen maniac wielding a shotgun with no context given for how this situation arose. In another case, Holmes finds a model of an Aztec temple which forms part of a larger contraption. But when he connects the two, the following scene suddenly sees Holmes inside the model, at which point you’re forced to proceed through an interminably long sequence of half-baked environmental puzzles. It’s absolutely all over the place.

My only conclusion is that Frogwares’s ambition got the better of it. It seems to have gone completely mad and attempted to include every idea it had into the Devil’s Daughter. The result is a brown and broken mess that I never once enjoyed. It’s a smorgasbord of nonsense, a cornucopia in which all the food has rotted. And what do we do with something rotten? We put it in the -

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.